For most of us, human faces are captivating. They convey much of our identity and are not easily changed. Paying attention to faces allows us to share information, judge others’ moods and distinguish friend from foe, often without effort or awareness. We see faces when they are not there – in objects, clouds and food. Even newborn babies will shift their gaze to follow a face around the room, despite having really poor vision. All this may be down to the mysterious nature of face processing in our brains. Face recognition is different to object recognition. Faces are processed holistically – as a coherent whole, rather than a group of parts – and are susceptible to illusions, such as inversion effects, that objects aren’t affected by. Faces also activate specific parts of the brain which objects don’t, including an area known as the fusiform gyrus, later coined the ‘fusiform face area,’ FFA. The system for processing faces seems to be specialised, but researchers can’t agree on what it is specialised for. Some researchers advocate a face-specific view, arguing that this recognition system is specialised for upright faces, and is never used for any other entity. Others take the expertise view, arguing that the system for face perception is not specific to faces, but to very similar members of a category that an individual has learned to swiftly distinguish.

Looks like a normal face?

In support of the expertise view, experts on various categories (such as dogs, handwriting and even chess moves) have been shown to process the objects of their expertise in a manner similar to faces – showing face-like inversion effects and using the FFA. However, finding expert like these to study properly is a problem, as acquiring such expertise takes a long time, and is difficult to measure.

Not quite! When the face is upside-down (inverted), tampering with the internal features is much more difficult to notice. Quite obviously, this became known as the Thatcher illusion, although it works on any face – but almost exclusively on faces.

With thanks to Jonathan for the image.

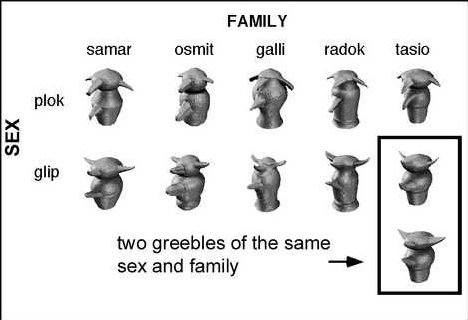

To avoid the variation amongst real-world experts, researchers came up with a novel way of making ordinary people into experts with the same level of ability as each other. They created Greebles – novel, computer-generated creatures, each with an individual identity and their own family. Greeble training has been shown to alter how people process Greebles: they stop using a piecemeal strategy and switch to a holistic one, with some research showing that they begin to activate the FFA.

If the expertise account is true, then problems in recognising faces should be accompanied by problems recognising objects of expertise – Greebles. In 2014, a paper tested this prediction on two neurological patients, Herschel and Florence*, who both have acquired prosopagnosia – they can’t recognise faces, but they weren’t born that way.

Greebles were created to test the effect of acquiring expertise on the face and object recognition systems

Florence, Herschel and a group of typical people all underwent a Greeble training program and a face recognition program. Obtaining Greeble expertise requires the ability to identify individual Greebles, and the families to which they belong. The faces test required the correct identification of a number of computerised faces by name.

Florence and Herschel were just as good at controls at identifying Greebles, showing 97% accuracy for identifying individual Greebles. They also showed the same pattern of performance as the typical participants during training. This means that there were not starting Greeble training at a disadvantage, and probably learned to recognise Greebles in the same way as controls.

As expected, Florence and Herschel were very poor at face recognition. Their abilities can be contrasted with that of another patient, C.K., who could recognise faces but not objects, and did not manage to become a Greeble expert in an earlier study. Seeing these opposing patterns of performance implies that Florence and Herschel’s success wasn’t due to Greeble training being too easy.

The ability of prosopagnosics to become Greeble experts suggests that face-specific processes are not necessary for Greeble expertise. This in turn implies that there is more to face perception than simply being an expert.

This wasn’t an imaging study, so it is still possible that Florence and Herschel achieved the same level of Greeble performance by using a different strategy to controls, allowing them to develop the ability to recognise Greebles expertly, albeit in an atypical way.

The structure of the Greebles does resemble a face, so it is possible that they can be treated as faces, but do not have to be. Treating Greebles as faces may have been the more efficient strategy for typical participants, but treating them as objects may have worked just as well. If this was the case, it would not easily explain Florence and Herschel’s persistent struggle to recognise faces, rather than learning a different strategy for faces, served by the object system. Out in the real world, Florence can identify people by their bodies, and W.J., another prosopagnosic, can distinguish each member of his flock of sheep, recognising sheep faces as well as typical farmers. Their ability to expertly distinguish anything other than faces is striking, harrowing, and seems to advocate a unique status for face processing.

The authors of this study suggest that previous findings that faces areas became involved in Greeble processing might not have separated face- and object- areas properly. Previous research found that, although real-world experts activated face recognition areas when viewing the objects of their expertise, object recognition areas were activated too. It could be that, in typical individuals, the systems for face and object recognition work in concert, but that the deficits experienced by these atypical cases mean that these systems are not able to work together to compensate for problems in one area. This possibility does not seem to have been explored.

Whether face processing is truly different to object processing is still uncertain, but Greeble training has suggested that recognising our loved ones is probably not simply a matter of expertise.

*Pseudonyms given by the researchers

Oh this brings back a couple of memories! Also fitting, as my last blog post says: “I have been known for falling asleep onto a paper about Prosopagnosia before.”

I promised myself to never hear the word “Greebles” again, however this is beautifully written.

LikeLike